Get in the Fight: Improving the Education System in Atlanta

W.E.B. Du Bois (New York Public Library)

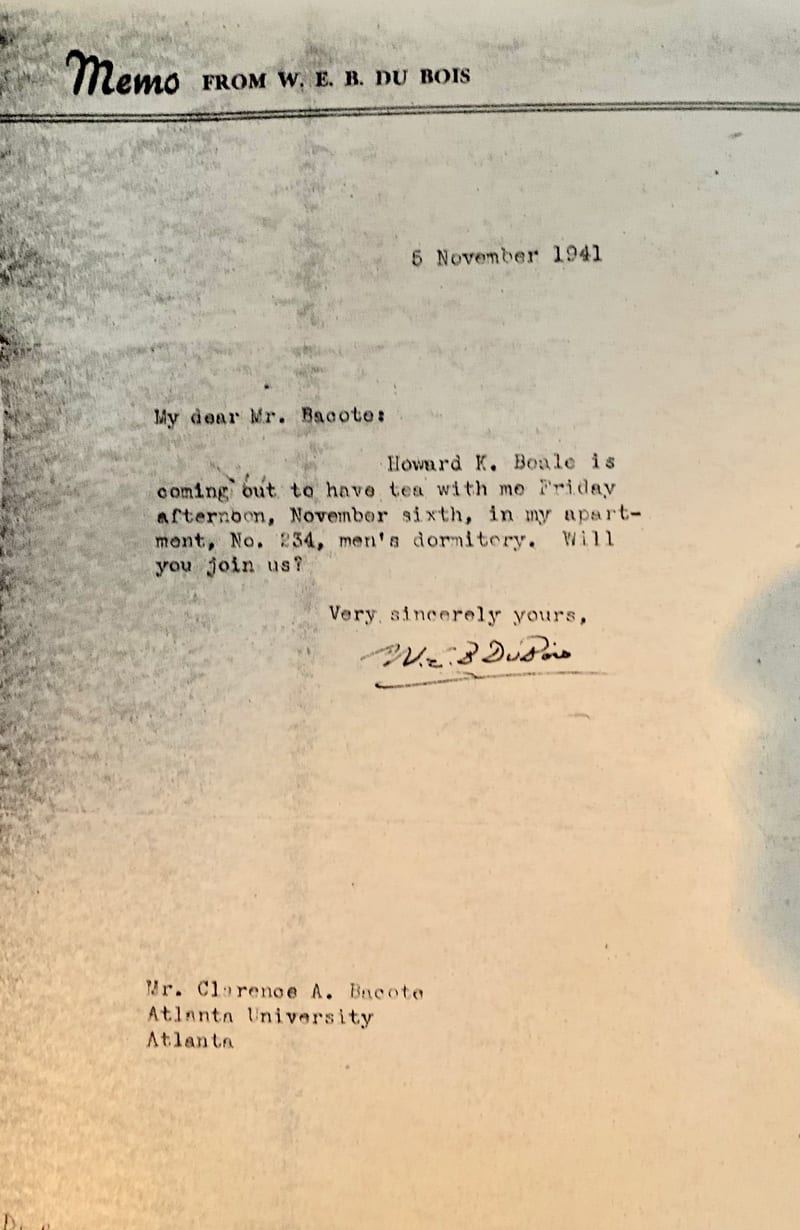

Nov. 6, 1941, was a Friday. Perhaps it was a cold, wintry day. The trees’ naked branches, embellished with snow, standing with the same strength and grace of W.E.B. Du Bois and Dr. Clarence Albert Bacote. The note above reads that these two historians, civil rights/political activists, African American leaders were going to have tea as a “symbolic protest.” I visualize the trees remaining still despite the occasional gusts of wind, much like these giants, who stood poised and ready to show their grace during turbulent times of inequity.

W.E.B. Du Bois needs no introduction here: in his time, he was a leading Pan-Africanist who co-founded the NAACP in 1910 and wrote The Philadelphia Negro, The Souls of Black Folk and Black Reconstruction in America. Clarence Albert Bacote was an Atlanta University professor and department chair who educated and organized black voters in Atlanta in the mid-1940s; wrote The Story of Atlanta University: A Century of Service, 1865-1965; served as Director of Citizenship Schools for NAACP’s Atlanta chapter, served as Atlanta All-Citizens Registration Committee (ACRA) chair; and was my grandfather.

Dr. Clarence Albert Bacote, affectionately known as Popeye, was our family’s gentle giant. I’m still in awe at how many people have told me that the loving man who made all seven of his grandkids a Black Cow (coke and ice cream) every time we entered his home, gave just as much attention to thousands of graduate students. I’m not surprised when I’m told that he was able to teach his lessons without referring to a book. We all remember him sitting in his leather reading chair for hours, protecting his memory and thinking skills through mental stimulation. I can still visualize the cherry stem pipe registering a weirdly peaceful, smoky scent throughout the house. At the age of 11, I recall how I fed Popeye tapioca pudding at his bedside in the hospital. It was his favorite dessert. Even as he was near death, there was a sense of calmness in his eyes. Perhaps because he and Du Bois were such heroes. They were leaders who found the strength to persevere and endure despite the brutal boycotts, demonstrations and marches protesting segregation in the segregated South.

After his death, my family gave many of my grandfather’s letters and files to Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library. The “tea” invitation pictured here was one of the historical mementos we kept. I am so appreciative of my aunt and father who realized early on that these memories must be preserved and for the university for continuing to honor his legacy. I remember it like it was yesterday –mama, aunt Lucia Jean and daddy going through stacks of papers and over a thousand books, delegating how everything should be decluttered—boxes had to be labeled, piles had to be made, items had to be organized into “Donate to Woodruff” or “Family Keepsake.”

After his death, my family gave many of my grandfather’s letters and files to Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library. The “tea” invitation pictured here was one of the historical mementos we kept. I am so appreciative of my aunt and father who realized early on that these memories must be preserved and for the university for continuing to honor his legacy. I remember it like it was yesterday –mama, aunt Lucia Jean and daddy going through stacks of papers and over a thousand books, delegating how everything should be decluttered—boxes had to be labeled, piles had to be made, items had to be organized into “Donate to Woodruff” or “Family Keepsake.”

In W.E.B. Du Bois,’ book The Fight for Equality and the American Century, I was able to get the details that led up to the note Du Bois sent to Bacote. Du Bois was denied the opportunity to attend “another” historical convention at Atlanta’s Biltmore Hotel in 1941. The Southern Historical Association (SHA) excluded blacks from the meeting. Howard Beale, a white American historian and University of North Carolina professor, led a charge to desegregate the convention. The management of the hotel modified the racial ban to apply to public restaurants during the convention. However, the committee was afraid that Georgia professors, employed by state institutions, would be released by Governor Eugene Talmadge for eating in restaurants with negroes. The local white SHA membership pleaded with Du Bois and others to refrain from attending luncheons and dinners. Howard Beale protested by inviting Du Bois and Bacote to breakfast or tea at the Biltmore. Du Bois proposed instead that he join them for tea in his graduate dormitory apartment. Du Bois resigned from SHA three months later.

In other words, because of segregation in Atlanta restaurants, Du Bois and Bacote were politely asked not to attend the 1941 SHA annual meeting, which leads me to the point of this article—Du Bois and Popeye were not at the table for the meeting, they had not even been invited, but were still engaged in the fight. Today, we are in the midst of another fight: an educational crisis for students of color. Yes, a majority of leadership in education reform is white, but unfortunately, black people are often still not present during decision-making time. We all agree with that this is nothing new. African American clergy, local politicians, business and education leaders, community members, moms and dads: as we attempt to address social and systemic injustice, let’s begin with increasing our involvement with our local school districts to improve education and ensure that our children are prepared for life in the 21st century. Let’s take a stand to ensure our children are afforded the tools to succeed. That starts with high-quality schools, rigorous curriculum, effective teachers, impactful guidance and mentoring—and holding schools and teachers accountable. We can become engaged by serving as mentors, attending school board meetings, joining our local school board, providing financial support to school fundraisers and writing elected officials. You can also engage directly with local organizations such as UNCF and Atlantans for Excellent Schools. I urge everyone in our city to read UNCF’s Lift Every Voice and Lead (https://cdn.uncf.org/wp-content/uploads/reports/GrasstopsToolkitReport_6x9 _4-17J.pdf) for a better understanding on how you can get involved and use your influence to help alleviate the education achievement gap in our city.

Over 600 influential African American leaders across the United States, often referred to as “grasstops” leaders were surveyed to assess the potential for African American leaders to positively influence education reform. The result of the survey resulted in ten tips you can use for your own community engagement and advocacy efforts. The time to engage is NOW. Even if your child is not old enough for school or has graduated from high school, get in the fight. Even if you don’t have children yet or have no plans to become a parent, the quality of education has a lasting

impact on your community’s future—get in the fight:

- Engage with your local and state representatives

- Write a blog post or Op-ed about education reform or your own personal experiences

- Participate in media reviews

- Use social media to reference K12 education reform and the need for high quality schools

If we don’t collectively speak up for what we want out of our schools, our voices will never be heard. If we don’t demand higher standards, we’ve failed our children. If we don’t get in the fight, we have failed DuBois and Bacote.

In the spring of 1942, Du Bois addressed the student body of Vassar College and Yale University. He spoke of “The Future of Africa in America” and “The Future of Europe in Africa.” He warned them, “We are only deceiving ourselves if we try to think that the solution of the problem of these millions of black folk in America is going to cost us nothing.”

As I think about Popeye’s peaceful gaze the last time I saw him alive, in the hospital bed, I believe now that he was pleased with the work he had done in his lifetime. One of his main plights during his life was centralized on voter registration—particularly in Atlanta. As a result of his efforts, the number of black registered voters in Atlanta increased from 6,976 to 21,244 in less than five months. Just as Popeye urged his fellow Atlantans to be involved in the democratic process back in the 40s, I’m urging you to become involved in education reform in our city now. He’d taught in the history department at Morehouse College and mentored hundreds until his death on May 1, 1981. What saddens me is that what transpired on Nov. 6, 1941, in Du Bois’ graduate dormitory apartment is not the vision for where we are now … 78 years later. Our educational system is still in a crisis. We must invest in our brown and black children by building a foundation if we are going to break the cycle of failing our children. We have fragmented schools with overloaded staff and only hypothetical enrichment programs, but what are we gonna do about it?

Tea, anyone?

Kelli Bacote Ross is the community engagement manager, K-12 Advocacy for the UNCF Atlanta office. Kelli is a veteran leader with a distinguished 24-year history of working in public education. She entered the education profession as a kindergarten teacher and has extensive experience assisting instructional personnel and managing stakeholders. Kelli has a bachelor’s degree from Howard University and a master’s degree in early childhood education from Emory University.

Kelli Bacote Ross is the community engagement manager, K-12 Advocacy for the UNCF Atlanta office. Kelli is a veteran leader with a distinguished 24-year history of working in public education. She entered the education profession as a kindergarten teacher and has extensive experience assisting instructional personnel and managing stakeholders. Kelli has a bachelor’s degree from Howard University and a master’s degree in early childhood education from Emory University.