The HBCU Effect®

The HBCU Effect® research series seeks to understand, validate and promote the success of historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) to develop a counter narrative that fully illustrates the value and competitiveness of our institutions.

Uncovering More of our HBCU Truth: UNCF Introduces “The HBCU Effect”

America’s historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) were founded to educate Black citizens who were restricted from attending predominantly white institutions of higher education. Four HBCUs that persist today were founded prior to the Civil War (Cheyney University of Pennsylvania, University of the District of Columbia, Wilberforce University and Lincoln University); however, post-emancipation, HBCUs rapidly spread across the southeastern United States, with most of the earliest institutions providing the necessary educational needs of the day: vocational and teacher training. In fact, the first Southern HBCU, Shaw University, was founded in 1865 in Raleigh, NC. Today, more than 90% of these important and distinct institutions remain rooted in southern states.

Over the subsequent century and a half, HBCUs have been indispensable to the larger Black experience in America, simultaneously shaping the broader tapestry of the country. Despite attacks that question their purpose in today’s society, they are beloved by those who are their beneficiaries. Despite never having adequate resources, they have continued to educate a significant portion of America’s Black middle class. And despite the constant myths and mistruths that constantly circulate about them, HBCUs press forward with a mission as urgent today as it was 150 years ago. Their steadfast mission to serve underserved communities was evident in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic as HBCUs across the nation mobilized to provide shelter, operate food pantries and offer financial relief for not only their students, but local communities. As they have in the past, HBCUs today continue to give back to the community at large in more ways than just through education.

These vital institutions, and the communities they serve, deserve more accurate portrayals, deserve more resources and deserve to have their full purpose and impact shared and explained responsibly. In our efforts to serve these institutions, students and communities, UNCF through its Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute (FDPRI) launched a body of work called “The HBCU Effect,” with the purpose of housing and distributing HBCU-focused research studies.

Download the report here.

“The HBCU Effect” demonstrates the historical and present-day impact of institutions that, despite being tremendously under-resourced—combating historical underfunding, inadequate endowments, biased media messaging that either ignores the institutions or lazily reports uniformed and inaccurate information with little to no context of institutional history, inequitable data reporting practices, and serving largely underserved populations—and serving a substantially low-income and first-generation student population which has largely been left behind by the K-12 system. HBCUs consistently overproduce, accounting for only 3% of public and not-for-profit institutions, yet enroll almost 10% of African American college students nationwide, while yielding 17% of the bachelor’s degrees and a quarter of the STEM degrees earned by Black students.

Decades of historical and contemporary research tell us that HBCUs have been and continue to be the catalyst for educational, economic, cultural and societal gains for African Americans and, to a degree, the rest of the nation and the world. Preparers of the Black professional class, providers of economic opportunity in their communities, molders of cultural originality and cauldrons of intellectual unrest that spurred the evolution of American society, HBCUs have been among the most American of institutions by educating citizenry who have held the country accountable to its founding ideals and principles.

Returning on the Investment1

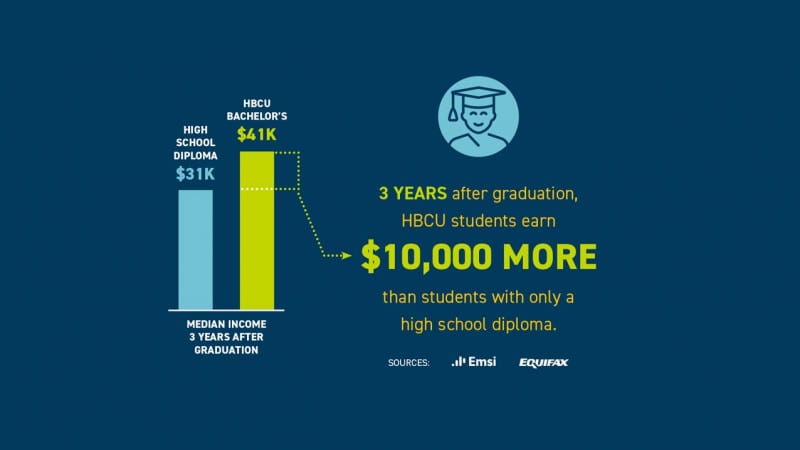

Education has always been considered one of the great equalizers in the United States. Research on the value of a college education clearly demonstrates that education continues to play a major role in helping Black students climb the economic ladder. Data from the UNCF Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute (FDPRI) reinforces this, revealing that just three years after graduation, HBCUs students earn $10,000 more annually than students with only a high school diploma.

Equipping First-Generation Students

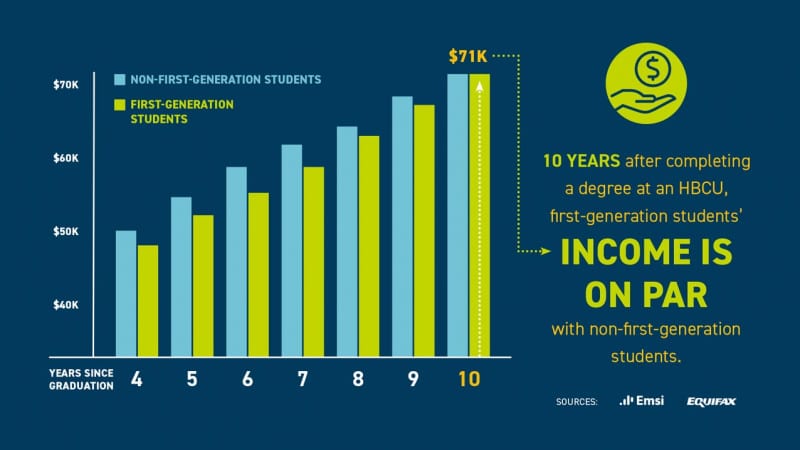

First-generation students often have a more difficult time navigating the higher education space and securing a job upon graduation.2 However, 10 years after completing a degree at an HBCU, first-generation graduates’ income is on par with non-first-generation graduates. This is important to note, as most predominantly white institutions report lower income levels for first-generation graduates.

Transforming Generations

Just as HBCUs were instrumental in creating the Black middle class, they continue to improve the socio-economic mobility of Black Americans. More than 70% of HBCU students are federal Pell Grant-eligible; however, HBCU graduates surpass their family income level (with the Pell-eligibility threshold being $50,000) six years after graduating, demonstrating the positive effect HBCUs have on intergenerational socioeconomic mobility.

Closing the Gap

For those who question the legitimacy of an HBCU education, it is critical to note that Black HBCU students achieve an income on average surpassing Black college graduates. Between two and eight years post-graduation, they climb the income ladder, out-earning the average Black graduate by year three and meeting the average income for white graduates by year eight. Although the income disparities between white and Black graduates still exist, HBCUs are playing a major role in helping close the earning gap.

Download the report here.

1 The data used in this analysis were provided by Emsi and Equifax. The data is comprised of 21 HBCUs that are a part of UNCF’s Career Pathways Initiative.

2 Rubio, Lena, Candi Mireles, Quinlan Jones, and Melody Mayse. Identifying issues surrounding first generation students. American Journal of Undergraduate Research 14, no. 1 (2017): 5-10.